Cornell University Library Digital Collections

19th Century Prison Reform Collection

The creation of the 19th Century Prison Reform Collection was supported by the Grants Program for Digital Collections in Arts and Sciences, awarded to Katie Thorsteinson, doctoral candidate in the Department of English at Cornell University, in 2017.

The following introduction to the collection was written by Katie Thorsteinson.

Introduction

This digital collection exhibits several documents charting the emergence of the Auburn Prison System. In the early to mid- 19th Century, US criminal justice was undergoing massive reform. The state prisons which had emerged out of earlier reform efforts were becoming increasingly crowded, diseased, and dangerous. Consequently, the “Auburn System” was developed in New York at Auburn State Prison and Sing Sing Correctional Facility. The reformers believed the penitentiary could serve as a model for family and education, so sought a system that was more rehabilitative than harshly punitive. Prohibited from talking at all times, prisoners were confined in separate cells at night and then labored together during the day in workshops modeled on the industrial factory. This regimented work routine and enforced silence issued from American Protestant ethics and the increasingly capitalist logic of the emergent nation. Although this “silent” system was incredibly popular with many reformers across the United States and beyond (de Tocqueville wrote of it in Democracy in America), Pennsylvania had already developed a vying system. The “Pennsylvania System” discounted the industrial factory model of silent labor, emphasizing instead the redemptive and hygienic values of permanent solitary confinement with an artisan labor style. In fact, the Pennsylvania System first inspired the construction and management of Auburn Prison. However, the Auburn System eventually developed several key modifications. Slightly less concerned with the Quaker-inspired principle of non-violence, Auburn embraced a more Puritan ethic of just recompense. Disagreement amongst these reformers about the future of American incarceration was often vociferous and combative. Indeed, “the rivalry between them became one of the defining controversies of the Jacksonian period, through which Americans contested the meaning of citizenship and humanity in the Republic” (Smith 10).

While the Pennsylvania System was at first popular in the United States and England, by 1833 the Auburn System had been established throughout Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Washington DC, Virginia, Tennessee, Louisiana, Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, and even Ontario Canada. Only Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland retained the rival system. Meanwhile, a more bureaucratic controversy had been stirring between the New York Prison Association and the Inspectors of State Prisons. Both groups sought authority over prison management, and their complaints recorded in this collection reveal a degree of emotion exceeding even the early Auburn/Pennsylvania reformers. Kroch Library’s Rare and Manuscript Collections houses several very important documents that span 1826 to 1881, revealing the tensions and contingencies of history. This digital collection exhibits these documents somewhat chronologically, embedded within a summary and synthesis of these two central debates. A few stray fragments and images are included at the end to highlight the personal and political connections between the various reform movements of this period. Finally, the conclusion explores why this history matters for our contemporary debates about racialized mass incarceration. After all, these artifacts remind us how many directions we could have turned. While our contemporary prison system may seem necessary, obvious, and incontrovertible, it was once only a possibility. Information is mostly presented in essay format on this page, but you will find some annotations and hyperlinks by clicking on items. Where information cannot be elucidated by the artefacts in Kroch Library, you will find references to external archives and readings.

Before Reform

Prior to the Revolutionary War, the American criminal justice system was based on English common law (subsequently acquiring several civil law elements). Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, various forms of physical punishment or public shaming were applied to both trivial and brutal crimes alike. Even in this period, however, American courts tended to be less punitive than those in England where minor infractions like robbery were easily cause for death. This penalty was comparatively rare in the American colonies and pardons were typical. Although not published until 1943, the following book reproduces an example of the common law system in 17th Century England. "The Trial of Adrian Scrope" for regicide led to his execution in 1660, exiling his son to America where he renamed “William Throope.” Coincidently, New York’s twelfth governor and prison reformer Enos T. Throop was a descendant.

Moreover, while jails existed in the American colonies, they were not built to contain people for long periods of time. Instead, they were often used as temporary holding cells before trial and for the dispensation of these other forms of corporal punishment. In addition to the assumption that such techniques were more effective at preventing and reprimanding crime, colonial America struggled with a labor shortage that encouraged the speedy release of potential workers. Workhouses, however, did hold prisoners for longer periods of time. “Vagrants” or debtors were confined in communal cells at night and forced to work off their debts during the day. In either case, confinement in these “houses of correction” was not itself considered a mechanism of punishment.

After the American Revolution and the United States Constitution, however, confinement became both means and ends of criminal justice. (Though Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut had all inaugurated penal reforms in the years immediately prior.) With the Bill of Rights, Americans were guaranteed free speech, protection from unreasonable search and seizure, due process, a fair and fast trial by jury, freedom from excessive fines or cruel and unusual punishment. The spirit of the age swept into myriad social reform movements, especially regarding the law and government. Legal codes were standardized, and law enforcement was increasingly supervised. Many states were abolishing certain corporal punishments and restricting the death penalty, both considered holdovers from monarchical authoritarianism. These political feelings mixed with new religious fervor in the Second Great Awakening. While “political philosophers developed the theory of the social contract, and legal theorists used the language of citizen's rights,” the popular reform movements of the time “preferred the idiom of Christian charity and sentimental 'humanity'" (Smith 35). Punishment was administered privately and “humanely” whenever possible.

Moreover, as cities grew in the Industrial Revolution and with increased immigration from Europe, people began to reconceive the causes of criminal behavior. On the one hand, the rise in transient populations prompted many to think of criminals as contaminating outsiders rather than simply errant neighbors. On the other hand, many blamed polluted and sinful urban environments instead of essentializing about criminal types. “No longer a predatory beast,” the criminal “became a lost soul” (Smith 35). In the wake of these demographic shifts, older punishments failed. Exile merely exacerbated the spread of transient criminals and corporal punishment could not isolate them from the corruption of urban centers. Longer-term incarceration thus appeared the perfect replacement, especially throughout the Northeast. Of course, enslaved people were still tortured throughout this period in the most horrific and public ways. The prison reform movement thus marks the increased racialization of corporal punishment. Nevertheless, several documents at the end of this collection reveal the intimate connections between the prison reform and slave abolitionist movements as well as those working on behalf of veterans, the poor, or the mentally ill. For example, novel institutions like the asylum and almshouse were developing in tandem with the penitentiary. The Auburn Prison System directly inspired the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield.

All these reform movements were great experiments, and many approaches had to be abandoned or reconceived along the way. For example, most of these early reform efforts centered on altering the penal code. It was not until the 1810s that widespread construction of penitentiaries began after higher incarceration rates led to overcrowded gaols and, like most infrastructural projects, this process took time. Although Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail was renamed the country’s first state prison in 1790, construction was not attempted in Pennsylvania until The Eastern State Penitentiary which opened in 1829. Auburn opened in 1818, but the North Wing was not completed until 1821. It was this addition that really initiated the Auburn System as distinct from its forebear, and the South Wing was remade accordingly in 1823. The bifurcation of Pennsylvania and Auburn Systems is thus captured in the prison’s very architecture. Sing Sing was then constructed entirely on the Auburn model but did not open until 1826 and was not completed until two years later. Even during this period, reformers tended to endorse the mere fact of imprisonment and would not really begin to theorize various penal systems until the Jacksonian Era. The penitentiary has a particularly vexed history in the South, but the institution had finally taken hold by the end of the 1830s. According to Paul Cromwell, the Auburn System dominated largely because it was more cost-effective and sometimes even lucrative for the government.

But the Civil War and its aftermath reinvigorated these reformist movements across the United States. Few state prisons had been created or renovated since the earlier part of the century and several power struggles had developed between different administrative agencies. Moreover, the Reconstruction Era brought public attention to dilapidated and archaic antebellum prisons. These efforts to reform and standardize criminal justice thus constituted a larger project of rebuilding national solidarity. Even at the end of this century, however, reformers were still protesting the same overcrowded, mixed-gender, exploitative, and harsh conditions in prison. Relying heavily on new social “scientific” ideas, these “Progressive Era” reformers operated both under behaviorist models of correctional incentivization as well as eugenic theories about racial delinquency.

“One must not,” Michel Foucault argues, “regard the prison, its ‘failure’ and its more or less successful reform as three successive stages” (271). He explains further that

In a very strange way, the history of imprisonment does not obey a chronology… There was in fact a telescoping or in any case a different distribution of these elements. And, just as the project of a corrective technique accompanied the principle of punitive detention, the critique of the prison and its methods appeared very early on, in those same years 1820-45; indeed, it was embodied in a number of formulations which— figures apart— are today repeated almost unchanged. (Foucault 264-265)

In a very real sense, reformers always situate themselves as the before to a speculative after. The debates amongst these reformers inevitably reoriented their projects and the very momentum of these movements enlarged their scope, such that this “before” has spanned the existence of the penitentiary itself.

The Auburn and Pennsylvania Systems

Commissioned by the Pennsylvania General Assembly to revise the state’s criminal code, "Messrs. King and Wharton of Philadelphia, and judge Shaler of Pittsburgh” visited Auburn State Prison in 1826. Their follow-up letter seeking further information, along with similar requests from authorities in Ohio and New York Governor DeWitt Clinton himself, prompted Gershom Powers as the agent and keeper to issue this report. It outlines "the main principles and practice of this institution… in pamphlet form, suitable for general circulation," as well as to train newly appointed prison officers. Their letters are also included, revealing the questions that motivated prison reformers across the US Northeast: disciplinary methods, architectural design, general health and cleanliness, productivity and style of inmate labor, operating costs, recidivism rates, and convict population demographics. Following these, Powers gives an account of the construction, management, and discipline of Auburn Prison; a compendium of criminal law; an abstract of the contracts first made with local manufacturers; a report on the trial of an officer for whipping a convict; as well as a plan of the prison. Powers was a zealous advocate of the Auburn System, and his defense of it here illuminates key ideological differences with the Pennsylvania reformers. Be especially attentive to the rhetoric of subtle ridicule and self-aggrandizement in his report, a tone which is echoed back by the Pennsylvania System advocates in their Memorandum of a late visit to the Auburn penitentiary included later in this collection.

The Consensus

Despite their irreconcilable differences, however, Powers identifies a certain consensus between both schools of reform. Contrasting their own reformist ideals with those European criminal codes which remained “the relicts of barbarous ages fit only for engines of tyranny and oppression,” the Auburn and Pennsylvania models shared several key principles:

- Both believed, Powers writes, that “Crimes and punishments should be more exactly defined and fixed by the laws; less should be left to the discretion of judges.” Foucault describes this emphasis on impartiality and standardized procedure as the regime of biopolitics, a “concern with individualizing observation, with characterization and classification, with the analytical arrangement of space” (203).

- Although these reformers offered very different methods of ensuring isolation — Auburn known as the “silent” system and Pennsylvania the “solitary” system — both agreed it was of upmost importance to the general health, punishment, and moral improvement of the inmates as well as in the prevention of what Powers calls “conspiracies or rebellion.” Powers here insists that it “occasions them more suffering, and tends more to humble and reform them, than everything else without it.” During this time, pulmonary tuberculosis (or “consumption”) was the leading cause of death in the United States and this pamphlet frequently lists the number of prisoners who died of this disease. Many blamed the overcrowded gaols and county jails from which “filth and vermin” were often brought when prisoners transferred.

- While isolation provided these reformers with one means to prevent tuberculosis from spreading, another was in the enforcement of regular sanitation. When inmates first arrived, they were “shaved, their hair cut, their bodies cleansed with warm water and soap and thoroughly purified.” This report outlines in great detail the timetables dictating when inmates must wash before meals and after labor. This new obsession with cleanliness was further reflected in the maintenance of the building itself. “Great care was taken,” Powers explains, “by whitewashing and cleansing, to keep their cells and clothing pure and wholesome.”

- This very introduction of timetables was, moreover, a trend shared by both reform movements. As Michel Foucault famously argues, "The principle that underlay the time-table in its traditional form was essentially... non-idleness: it was forbidden to waste time, which was counted by God and paid for by men" (154). Nevertheless, the definition of non-idleness differed radically in both systems (Auburn preferring a system of silent labor modeled on the industrial factory, Pennsylvania instituting an artisan labor style in solitary confinement).

- More than merely a means of enforcing work, these timetables were part of the larger project of disciplinary control over the soul. Foucault famously observes how the “body as the major target of penal repression disappeared” in this period, replaced by “the entry of the soul on to the scene of penal justice” (8, 24). “From being an art of unbearable sensations,” he concludes, “punishment has become an economy of suspended rights” (11). Nevertheless, while his report emphasizes religious instruction, Powers’s description of a whipped convict suggests that bodily pain remained a central feature of penal discipline.

The Conflict

Solitary Confinement

Thomas J. Wharton sent this letter to former president James Madison April 18th, 1828, accompanied by his commissioners’ report to revise the penal code of Pennsylvania. He writes that the “subject of the first report has occasioned considerable discussion in this state and in Europe and a great difference of opinion exists... The opinions of candid and enlightened men upon this grave question are much to be desired, and I shall be anxious to learn how far your sentiments correspond with those expressed in the report." In his response, Madison praises Wharton’s detailed examination and expresses his support for prison reform:

Based on Madison’s response, the divisive question raised in Wharton’s first report seems to concern the relative benefit or harm of solitary confinement— the central conflict between the Auburn and Pennsylvania reformers. Madison is especially concerned with reducing the cruelty of penitentiary discipline and with the potentially harmful effects of solitary confinement. He enthusiastically supports the Auburn model, writing that a combination of moderate solitary confinement “with joint and silent labor, under the eye of a superintendent… seems to involve all the desiderata, better than any yet suggested.” Since Madison notes this is the “plan preferred in the Report,” it appears that Wharton and other early reformers in Pennsylvania were also critical of the model being developed in their state.

Recall that A brief account of… the New-York State Prison at Auburn includes a letter Wharton sent after his visit to Auburn Prison in 1826, also commissioned by the Pennsylvania governor to revise the state criminal code. Wharton was just as concerned with the issue of solitary confinement then, telling Powers how this "question is so particularly interesting in this state, where we have a prison exclusively adapted to solitary confinement, without labor, and another that can be only changed from it, by altering the plan of the unfinished part, that we shall be much pleased by hearing from you fully on this subject." Auburn had in fact experimented with a version of solitary confinement whereby prisoners were forced to lay supine all day contemplating their sinful deeds. But when several fell victims to physical and psychological maladies, the prison introduced the Auburn System of silent congregate labor in 1825.

However, in Memorandum of a late visit to the Auburn penitentiary (1842) included later in this exhibit, Fred A. Packard states his unequivocal support for the Pennsylvania model of artisan piecework and religious instruction which were not incorporated into Auburn’s early experiments with solitary confinement. This is what Packard calls “the modified form of solitude which obtains at our Penitentiary,” supposedly correcting any negative health effects observed at Auburn. With a tone similar to Gershom Powers’s subtle ridicule and self-aggrandizement, he writes of “several intelligent gentlemen, who… have been led to compare the two systems of solitary and social labor... but all with evident prejudice in favor of the latter.” He claims to have heard only two objections “to the Pennsylvania system… the inhumanity of solitary confinement, and the effects of it upon the mind."

He argues further that both objections "are entirely abstract and theoretical. Not a particle of evidence has yet been furnished that would influence the mind of an impartial and well-informed inquirer on either of the points; while reason and analogy combine to establish this one great principle, viz. that the first step in the process of reformation must be to separate the offender from the sight and intercourse, and, if possible, from the remembrance, of his evil associates.” This debate over the health risks and reformative capacities of solitary confinement defined the conflict between Pennsylvania and Auburn reformers, continuing over the next two centuries into our present moment.

Overcrowding

Even after the construction frenzy of the 1810s-1820s, overcrowding was a constant struggle for prison reformers and officials alike. This was especially problematic for the Auburn System where silence and separation were already difficult enough to enforce. According to the Prison Association in 1870, this issue struck “at the very foundation of our boasted 'Silent System of Prison Discipline,' as distinguished from the 'Separate System.’” Governor Throop reports as early as 1830 that there was “a greater number of convicts [at Auburn] than can be confined in separate cells,” whereas the agent of Sing Sing Prison reported that there were “unoccupied cells.” As a result, he issued this executive order for the transfer of prisoners in 1830. What a radical transformation had taken place over the previous half century, when congregate cells had once been the pre-Revolutionary norm!

This document thus reveals how the major weaknesses of the Auburn System reinforced the growing bureaucratization of prison management. As Foucault explains, "the prison had always been offered as its own remedy: the reactivation of the penitentiary techniques as the only means of overcoming their perpetual failure; the realization of the corrective project as the only method of overcoming the impossibility of implementing it" (268). If overcrowding was a problem inherent to the penitentiary and especially injurious for the Auburn System, solutions were offered on a secondary policy level: redistribute prisoners or build more prisons. The very same suggestion is offered two decades later in the Fourth annual report of the inspectors of State prisons of the State of New York (1852), this time sending prisoners to Clinton. Finally, Memorial of the Prison Association to the Governor of the State of New York (1870) notes how some prisons like Sing Sing had an excess of prisoners by this time, while Auburn and Clinton had open cells.

Communication of prisoners

Written by Fred A. Packard on behalf of the Philadelphia Society for the Alleviation of the Miseries of Public Prisons, this memorandum evaluates some key differences between the Auburn and Pennsylvania Systems. Foremost among them was the practice of solitary confinement which, as we have seen, entailed problems of overcrowding at Auburn. In this document we also see how the non-use of solitary confinement often led to communications between prisoners, which both groups believed injurious to criminal reform. Packard goes so far as to say, "There is no concealment, or palliation of [this] defect which has ever been regarded as prominent in the Auburn system." Indeed, he blames “the opportunity of acquaintance and communication" for several escape attempts he describes at length. An official at Auburn admits to the inevitability of "considerable undetected intercourse between convicts” and especially in those locations where “the code of silence does not apply.” Packard “could not but contrast this [situation] with a fact… from the late Warden of [Eastern State] Penitentiary (S.R. Wood) that he once saw three men [who] were all in the Eastern Penitentiary at one and the same time— each of them recognized him as he passed them; and yet neither of them knew the other, and could not have had the remotest suspicion that they had ever been so closely associated!" One of the most interesting features of this discussion is the way Packard analyzes the very architecture and material of the prison to show how the Auburn System permits communications between prisoners.

Power struggles

In the very beginning of his memorandum, Packard notes how immediate supervision over Auburn Prison "is entrusted to two general officers, viz. the agent, who has the sole management of the business operations, (such as providing food and fuel, making contract for convict labor and the raw materials for manufacturing) or, in a word, the economy of the prison; and the keeper, whose special province it is to have the custody of the convicts, and to supervise the police of the prison.” While Packard praises how they “are able to keep their respective functions entirely distinct," no such division of labor existed while Gershom Powers remained agent and keeper less than two decades prior. As if unashamed of this nepotism, Powers was married to Governor Throop’s half-sister Eliza Hatch and was later appointed Inspector of Auburn Prison from 1830 until he died one year later.

His son, Colonel William Powers, was such an enthusiastic supporter of the Auburn System that he moved to Upper Canada (now Ontario) where he supervised the construction of Kingston Penitentiary and served as deputy warden from 1835 until he was dismissed in 1840 after professional conflict with Warden Henry Smith. Their dispute concerned one of the central features of the Auburn System: the use of convict labor, which Smith blamed for greater communications between prisoners in his 1839 report. The Board of Inspectors also dissolved because of this “state of crisis” during which Clerk of the Peace, James Nickalls, made an unprecedented report to the government that he had "no faith in the efficacy of the Auburn system of discipline in effecting moral reformation of the convict, and deterring from the commission of future crime" (qtd. in Oliver 157). The dispute primarily regarded prison management and the hierarchy of power; Nickalls felt that the divisions in governance were so severe as to "imperil the best interests of the system" (qtd. in Oliver 157). Nevertheless, he was hesitant to remove Powers before the system was “more matured and established on a firmer basis,” fearing “the experiment as a means of punishment in Upper Canada [would] prove a failure" (qtd. in Oliver 157). The division of powers Packard praises here was likely instituted because of these conflicts at Kingston and other prisons modeled on Auburn.

Peter Oliver explains that, even though the Board of Inspectors was supposed to act as the primary restraint over the warden’s “ubiquitous control,” this check was negligible “since the Warden was its main adviser and link with the penitentiary. The warden's powers were pervasive” (155). At the same time, he argues that in “an institution as potentially explosive as a penitentiary, the division of authority is likely to have disastrous consequences" (Oliver 155). These debates over the distribution of power and styles of management would continue again and again over the following decades as revealed in the next two documents, Fourth annual report of the inspectors of State prisons (1852) and Memorial of the Prison Association (1870). A few years after Packard’s visit, this internal conflict expanded to include independent governing bodies concerned with the despotism of wardens and impotent fickleness of inspectors. But even before this expanded rift, Packard was already noting how "The New York prisons labor under very great disadvantage from the political influences that are continually interfering with their supervision, discipline, economy, &c. The fluctuation which must prevail in the policy and management of public institutions, where each political or party revolution gives them a new supply of officers or a new set of regulations, must be clearly injurious to the interests of all concerned."

On the one hand, public transparency and government intervention were thought important to prevent the tyranny of wardens. On the other hand, consistency and total authority were thought necessary for the very project of penal discipline. These particular power struggles were not repeated at Eastern State Penitentiary because their inspectors were appointed by the Pennsylvania court of Oyer and Terminer, a body at least theoretically independent of either the whim of public elections or the self-interest of state government: “Throughout the nineteenth century… all [the] administrators [of Eastern State Penitentiary] were appointed: the state supreme court appointed the inspectors; the inspectors appointed the warden, physician, and moral instructor” (Rubin 186). Moreover, unlike the separation of powers between agent and keeper at Auburn, the Pennsylvania System combined both roles in the position of warden. Nevertheless, Pennsylvania prison administrators were often embroiled in their own power struggles, most notably a small rebellion against the state legislature in 1861-1862 against the “Commutation Law” which required administrators at the two state penitentiaries and local jails to release inmates early for good behavior (Rubin 182).

Pardoning of prisoners

In fact, the early release of inmates for good behavior constitutes another point of contention between the Auburn and Pennsylvania Systems. In his memorandum, Packard decries "the undue exercise of the pardoning power” which he believes is particularly excessive in Auburn where “the effect must be altogether mischievous.” His disgust should be contrasted with the enthusiasm for pardoning powers expressed in the Fourth annual report of the inspectors of State prisons of the State of New York (1852), the next document in this exhibit.

Labor competition

Around this time Auburn introduced the manufacture of silk as a form of convict labor. Packard observes how the "success which has attended the experiment thus far is very encouraging… and there is every reason to believe that the whole operation of spinning, weaving and dying, will be completely successful.” But Packard also alludes to one of the greatest challenges facing advocates of the Auburn System: the industrial factory model of silent labor raised competition with local manufacturers who often protested prison construction in their communities and even filed lawsuits against the state government. This problem lingered for decades even though Packard writes that the “Legislature has restricted the employment of convict labor to those arts, trades, and manufactures, the products of which come to us chiefly by importation.” Evidently these restrictions did little to ameliorate the outcry against competition since more petitions of this nature are described in the next document, the Fourth annual report of the inspectors of State prisons of the State of New York (1852).

Discipline

This memorandum also points to how conflicts between the Auburn and Pennsylvania Systems could lead to consensus, as reformers attempted to correct the criticisms each posed. In Packard’s opinion, "the most important changes in the management of [Auburn] prison respect its discipline.” He argues “that the power to inflict corporal suffering upon convicts can never be conferred without imminent hazard. Perhaps it may be safe to affirm, that the infliction of stripes is a species of punishment which cannot well fail, of itself, to lead to cruelty. It is in its very nature an incentive to cruelty.” A similar view of corporal punishment is offered by the next two documents in this archive. Indeed, although Auburn Prison had once been infamous for what Packard described as “very cruel and excessive severity,” we learn that "the use of the whip was abolished among the females [in 1830], and in 1849 among the males except in cases of insurrection, revolt, and self-defense” (however, these “cases” were “left to the discretion of the officer immediately in charge” and the protection from whipping did not even apply to the local non-State penitentiaries). But even in 1842, Packard is convinced “that this mode of punishment is wholly laid aside… and that not a blow has been struck, for any cause, for several months. In lieu of this… they have adopted the cold shower bath, and find it, thus far, fully adequate to all punitive purposes."

The “cold head-bath,” as it was also called, involved the prisoner sitting naked on a box "formed somewhat like an easy chair.” “His ankles and wrists are securely confined;” continues Packard, then “the two halves of a board, cut out to fit the neck, are brought together under the chin, and thus confine the head, or at least allow it only a rotary motion. A tin tunnel, with a large or small tube, as may be expedient, is held at a proper distance above the head; and water, of the ordinary temperature, is poured through it in a steady stream directly on the top of the head. The quantity of water is regulated by its effect on the convict." As to these effects, Packard claims that, although "the expedient was first… regarded by the convicts as a very trifling affair, it was soon found to be a most effective method of correction. Cases occurred in which considerable fortitude was displayed through the use of a gallon or two of water; but not an instance has been known in which it was not, after a few minutes, utterly subduing to the most stubborn.” The contemporary debates over waterboarding as an extreme interrogation technique should alert us to the legacy of this disciplinary method and the hazy definitions of torture. While many of us will now cry out against waterboarding and its antecedent, the cold shower bath, some will still join Packard in believing that its substitution "for the cruel, degrading, and exasperating use of the cat-o'-nine tails is a most happy improvement."

Religious instruction

Packard’s assessment of religious observance at Auburn Prison contrasts sharply with those portrayals given in A brief account of… the New-York State Prison at Auburn (1826); Fourth annual report of the inspectors of State prisons of the State of New York (1852); and Fourth of July at Auburn Prison (1879). "In respect to the extent of religious influence in the prison,” he writes, “I was considerably disappointed. So much superiority has been uniformly claimed for this system over the other, in this point especially, that I anticipated a very obvious peculiarity. To my surprise, I learned that only one service is observed on Sunday... During the Sabbath, the chaplain may visit the convicts, but as he is not admitted to the interior of the cell, and can only converse with them at their cell-doors, it is difficult to make a visit, under such circumstances, either pleasant or useful. The prisoner on each side can overhear what is said, and this, of itself, would greatly embarrass the interview." Indeed, even those documents written from the Auburn perspective reveal a rhetorical preference for the economic rather than religious benefits of their model.

The New York Inspectors of State Prisons and the Prison Association of New York

When Auburn was opened in 1818, State Commissioners on construction transferred powers to a local Board of Inspectors appointed by the Legislature. Recall that Gershom Powers describes this office in A brief account of… the New-York State Prison at Auburn (1826): “This prison is governed by a board of Inspectors, residing in the village, who are appointed every two years by the Governor and Senate. They have no compensation, and are forbidden, by law, to make any contracts for the purchase or sale of any articles with the Agent of the Prison. They appoint the Agent and Keeper, Deputy Keeper, and all subordinate officers, who are removable at their pleasure. They are authorized and required, by several acts of the Legislature, to make and establish such rules and regulations, from time to time, for the government of the Prison, as they may deem necessary, and which the officers are bound to enforce and observe; all of whom are required to take an oath prescribed by law."

But in 1846, the New York State Constitution established the Inspector of State Prisons as an elective position. The amendment also abandoned the "former system of a separate government for each prison," explains the next document in this archive. This amendment held that three inspectors would hold office semi-sequentially for three years, with an election occurring every year for one seat. Their role was also to appoint wardens and keepers, supervising prison administration. Each one took special responsibility over one of the then-existing state prisons (Auburn, Sing Sing, and Clinton). They were required to oversee operations at their assigned prisons for one week every month and make joint visits to each prison four times a year.

In the years intervening his stint as President of the Board of Inspectors at Sing Sing and this constitutional amendment, John W. Edmonds founded the Prison Association of New York in 1844. The organization was formed to advocate for criminal defendants and people in prison, improve penal discipline and administration, as well as help with post-release reintegration. In the latter part of the century, they expanded these reformist efforts dramatically to create the National Prison Association (now the American Prison Association) in 1870 and then the International Prison Congress two years later. They also lobbied for the separation of convicted youth and adults (1864-74); helped institute the state’s first probation and parole systems (c.1875); opposed corporal punishment (1844-64); and fought against the exploitation of convict labor. It remains the only private body in New York with the power to conduct on-site examinations of state correctional facilities, reporting observations and recommendations to the government and public.

The following two documents in this exhibit reveal some of the tensions between the Prison Association of New York and the reorganized Inspectors of State Prisons. Following these controversies, the latter was abolished in 1876 by another constitutional amendment which instituted the Superintendent of State Prisons instead. This position was once again appointed by the New York Governor and confirmed by the Senate, a corrective to the partisan behavior of previously elected inspectors. The superintendent’s five-year term also allayed concerns about the fluctuating policies of three-year inspectors. These mid-century debates between the independently-operating Prison Association and publicly-elected Inspectors of State Prisons reveal important lessons about the divisions of power and interest in prison management. Ultimately then, as the debates between Pennsylvania and Auburn reformers began to subside in the wake of the latter’s obvious dominance, mounting bureaucratic conflicts began to plague the system.

Submitted to the New York Senate in 1852, this report records the observations of state prison inspectors. The document is overwhelmingly confident and conciliated with the operations at their respective state prisons. They claim to "feel highly gratified in being able to state that all the institutions under their charge have been favored with usual health, while their pecuniary condition and the mild yet salutary discipline reflect credit upon the subordinate officers to whose hands they have severally been committed." This tone immediately alerts us to the justified concerns of Prison Association members who believed these inspectors offered little in the way of critical oversight or intervention. Indeed, the inspectors seem to echo this concern themselves when they explain that "Like most other places of public trust and emolument, from long custom and confirmed habit, these offices are sought for and demanded as the reward of political influence and partisan services, and the tenure by which they are held is almost if not entirely dependent upon the fluctuation and changes of political power in the State. So long as the law regulating these appointments remains as at present, this state of things can scarcely be avoided, and the Inspectors must suffer an embarrassment from this source, until the Legislature shall provide some adequate relief by an alteration of the law."

They refer here to the 1846 amendment of the New York Constitution which made the inspector an elected position rather than appointed by the governor and confirmed by the senate. Nevertheless, despite admitting that this law suffers them embarrassment, their partisan bias is patently evident in this annual report which presents everything optimistically from the “more liberal exercise of the pardoning power,” to the “small addition of crime in our State,” and even increased mortality. Whatever their institution, they find in all these matters "a much better result than has ever been exhibited by this prison in any previous year since it was established.” They go on to claim that the "decreased amount of punishments in all the prisons, and the vastly improved state of the government, are to be attributed more to the humane system of discipline, the efforts made for moral and intellectual improvement, and to the better manner in which the convicts are clothed and fed, than to any change in the characters of the persons received." And, despite decades of failing the same prediction, all seem confident that their respective prisons "will eventually be able to maintain [themselves] without aid from the treasury of the State."

As evidenced by the following document in this exhibit, Memorial of the Prison Association to the Governor of the State of New York (1870), the dangers of mixing electoral politics with this office became the central conflict between these two governing bodies which lasted until the reversal of this amendment in 1876. Throughout this Fourth annual report, inspectors and wardens share a recurring opinion: The Prison Association should butt out of their business. Under a section titled "Prison Association," they describe "another attempt of a committee… to usurp [the warden’s] authority and interfere with his management of the prison… the warden [was] in pursuance of the recorded rules and regulations of the Inspectors, and his conduct merits an expression of our approbation as a prudent and faithful officer." These inspectors further claim that the action carried out “by the Prison Association is predicated upon a provision of their charter which was granted previous to the adoption of the Constitution." In other words, these inspectors felt that the Prison Association, founded two years before the amendment, was now acting extrajudicially. Moreover, these inspectors claim that for the two intervening years, “their labors were certainly unattended with any benefit to the State, the prison, or the convicts.” Sing Sing was severely in debt, labor productivity was down, and cruel punishments were implemented routinely. The Legislature had certainly incited a riot!

Apparently in direct response to criticisms raised by the Prison Association, these inspectors declare that they "earnestly court investigation. We have nothing to disguise, and there is not a single feature in the present management or discipline of any of the prisons, we would not gladly expose to public view. Our prison doors are open to the public, and hundreds visit them daily from almost all parts of the world." They go on to describe their own performance most favorably:

"An inspector always in charge, keeps constant watch of the provisions and sanitary treatment, listens to the complaints of every convict, and compels every officer faithfully to perform his duty. Such is the condition, and such the management of all the prisons, and we doubt if it is within the scope of human wisdom to devise a more judicious or humane system for the safe keeping and moral improvement of this erring class of mankind, than we are now laboring to carry out under the law of 1847. With our knowledge of the past and present, we shall long hesitate before we consent to have the present prosperity disturbed, and a system of mild and salutary discipline, which has been perfected by patience, forbearance and practical experience, destroyed by the meddlesome interference of any irresponsible association."

These inspectors finally appeal to flattery and groveling, as they wonder whether "the Prison Association really imagine[s] that [it] possess a co-ordinate power in the management of these institutions.” They claim it “an act of charity upon the part of [the Legislature’s] honorable body to disabuse them of that impression, which would relieve prison officers from much uncourteous interference and the expense and trouble of further litigation." (Other interesting aspects of this report include mention of the statewide “change of [prison] chaplain… [to]the Episcopal church” and the use of “phrenologists… to examine the heads of convicts by way of ascertaining if they had been rightfully convicted.”)

In their letter to Governor John T. Hoffman seeking "an amendment to the Constitution," the Prison Association calls the inspectors de facto "governors of the prisons and controllers of the system, subject to no supervision or inspection, except such as the Legislature may from time to time direct, and that of the imperfect power given to this Association. Every year one of them is thrown into the arena of party politics. They have an appointing power of about 200 subordinates, to whom about $220,000 a year are paid in salaries, and they are thus, from necessity, compelled to become in some measure, a political partisan body." Admitting that their proposed remedy “is a radical one, involving no less than an entire change in the organization of the government of prisons,” the Association also explains that it “received the unanimous sanction of the Senate, but was not acted upon in the Assembly.”

They note "how far short of attainable results, both in finance and discipline, our State Prisons have fallen" and how rates of incarceration had rapidly increased after the Civil War. "Under the former Constitution,” they explain, “the clerk of each prison, whose duty it was to keep the accounts, was not, as he is now, appointed by the Inspectors, but derived his office from the Governor and Senate, and being thus independent of the Inspectors, he constituted a check upon them, and in some degree a supervising power. But under the present system even that supervision is gone." They particularly lament the inspectors’ neglectful and inconsistent financial reports which were submitted to the Legislature. Striking back with the same argument of non-improvement the inspectors had once thrown against them, the Prison Association also complains how “no new measure for reformation has been adopted by the Inspectors” since the 1847 amendment. They similarly point out how the inspectors had failed “to erect 35 separate cells for the 'incorrigibly disobedient'” and also to pay “six per cent interest… to the convict on his discharge… [for] all moneys [he] brought to the prison,” even though both requirements had been enacted twenty-three years prior. They also note various attacks on officers at Auburn, Clinton, and Sing Sing; labor strikes at Auburn and Sing Sing; and escape attempts at Clinton. Ultimately, they claim sanctimoniously that these inspectors proved how the 19th Century “reformation of prisoners lived [only] in theory, not practice."

Instead, they propose a “Board of Managers of Prisons” to absorb these responsibilities, "to be composed of five persons appointed by the Governor, with the advice and consent of the Senate, who shall hold office for ten years." A series of letters between the Prison Association and the Office of the Inspectors of State Prisons are appended to this document, ending on particularly sour note. The Prison Association also lobbies in this letter for better libraries and educational programs for prisoners; the standardization and reduced severity of disciplinary methods; as well as better treatment and proper reallocation of the “insane.”

The Attachment to Reform

Taken together, the following two documents reveal America’s attachments to prison reform by the end of the 19th Century. National identity was now so deeply entrenched in this spirit of reform that the movement could not help but continue and required reformers to, paradoxically, declare their own previous effort a failure.

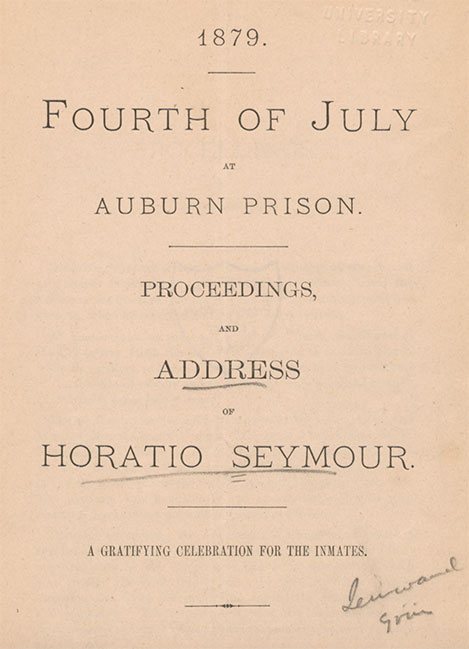

Consider the patriotism lavished on this 4th of July event at Auburn where prisoners surrounded a platform "handsomely and appropriately draped with National flags, over a portrait of Governor Seymour.” Indeed, to “the left of the platform was the full Forty-ninth Regiment Orchestra." Such "A Gratifying Celebration for the Inmates" on Independence Day should alert us to the deep associations between the penitentiary and the post-Revolutionary period. Few other religious or national holidays involved such festive ceremonies at any state prison, and few institutions were so favored by the former governor’s appearance. Indeed, his address included in this pamphlet blends together Christian faith, American allegiance, and prison reformism.

As if to echo the pursuit of happiness etched into the Declaration of Independence, he declares that “hope is the great reformer” and “despair is the unpardonable sin.” Moreover, he embraces the all-American bootstrap ethics of individuality and hard work: “it should give hope and consolation to all to feel that they can, in the solitude of the cell, or in the gloom of the prison, by thought, by self-examination, make the past, with its crimes, its errors and its sorrows, the very means by which they can lift themselves into higher and happier conditions.” Finally, in the tone of constant-campaigning that marks the American political speech as a genre, he claims to have done all he “could to gain the passage of laws which enable [them], by good conduct, to shorten the term of [their] imprisonment,” and would have liked them to receive “a share in the profits of [their] labor.”

This document praises the event’s success, especially the appreciation from prisoners who all “strictly observed” the rule of silence except when their “gratitude and satisfaction were earnestly expressed in prolonged applause." In apparent pursuance of the “silent system,” “not even a cough or a shuffle of the foot was heard among all the thousands and more men.” “As may be inferred from the language of the speaker,” it is further claimed, “his words sank deep into the hearts of his hearers, and in many instances drew tears of regret and repentant sympathy from those who, although confined as criminals, yet have the feelings of men and are susceptible to the better influences when rightly approached.” Yet, while this 1879 pamphlet recounts health and happiness during a festive event, the next document in this exhibit presents a rather dreary picture of New York penitentiaries only three years later.

Josephine Shaw Lowell, described by a biographer as the “grand dame of the social reformers,” is best known for creating the New York Consumers League in 1890. As this document makes clear, she was also instrumental in the rejuvenated prison reform movement of the late 19th Century. She calls the New York county jails badly constructed and “crowded to overflowing; men, women and children, the convicted and unconvicted, associating in idleness.” "The Penitentiaries,” she argues, are “scarcely better.” Lowell takes focused aim at the Prison Association which, as this exhibit has documented, was one of the fiercest critics of penal administration only a decade before. She demonstrates how the Prison Association had failed to justify its claim in an 1879 report "that the 'Onondaga County Penitentiary has its industries and supervision as well directed as any in the State.'" Indeed, this is one of the prisons she critiques most forcefully.

Her major concern is the treatment of women in prison, noting how "during the year 1880, two hundred and eighty-five women, between the ages of fifteen and thirty years were [incarcerated] by the laws of the State of New York.” Thus, proving the magnitude of the problem, she further cites an 1880 report of the State Board Visitors to the Fulton County Poorhouse: “‘Another great defect of this institution in its present arrangement is the common mingling of the sexes.” Lowell explains how this arrangement has led many women in prison to become pregnant and give birth to multiple “generations of paupers!”

Her condescending tone seethes into outright racism when she recounts how “the last of the four generations is a bright-looking mulatto… Do the tax-payers of the Fulton County wish this thing to continue to the fifth and sixth generations? God forbid this County should breed paupers as well as support them.’” Her manifesto evidences the confused mixture of behaviorist and eugenic theories about crime popular at this time, stating that “it was conclusively proved [in an inquiry made by the State Board of Charities] that vice, pauperism, idiocy and insanity are to a great degree hereditary.” But with undying faith in policy reform, she also claims that in “other Countries and in other States, it has been possible to rescue such women by removing them from the bad influences and the temptations which surround them and subjecting them to the discipline and kindly care of their own sex. In our own State, where personal pity has led to the founding of private refuges and reformatories, many of these unhappy women are reclaimed, but whenever it is their cruel fate to fall under the power of the law… they are thrust into the vilest companionship and are taught a deeper infamy than they could otherwise have learned."

Although ostensibly a defender of women in prison, Lowell actually normalized the rhetoric of female victim-blaming (for we may safely assume that many of these pregnancies were the result of rape or coercion). Still she worked towards some honorable goals, imploring the Legislature to “establish an institution for the custody and discipline of vagrant and disorderly women under the charge of [female] officers.” She also sought “a systematic course of instruction” under which some “women might be reclaimed, and the State saved from great future expense.” Her combination of behaviorist and eugenic theories was paradigmatically American at the turn of the 19th Century, as many were calling for radical state intervention over reproductive life or what Michel Foucault called biopolitics. Although increasingly doubtful about the reformative capacities of individuals, they hoped the prison would reform the social order as a whole. This document thus reveals both the redirection and consolidation of prison reform as it incorporated new social “scientific” theories that only served to further expand state powers. The so called “Progressive Era” of prison reform simply offered a new face to a movement already deeply woven into the American fabric.

Prison Reform Today

These 200-year-old debates about criminal justice reform are repeating today under the different circumstances of racialized mass incarceration. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander famously argues that the prison— far from simply "another institution infected with lingering racial bias"— has become "the primary vehicle of racialized social control in the United States" since slavery and segregation (11, 4). Alexander is not so forthcoming, however, about the precise relations between these racial regimes— often calling them "metaphorically" the same or "strikingly similar," sometimes detailing a more causal relationship. The tagline to Ava DuVernay’s documentary, 13th, about the constitutional foundations of the plantation-to-prison pipeline appears more direct: "From Slave to Criminal with One Amendment." The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, of course, ended legal slavery in the United States "except as punishment for a crime" (sec. 1; emphasis added). This constitutional loophole, Kevin Gannon explains, is “there to be used as a tool for whichever purposes one wants.” As the film details, however, these purposes have been largely economic. The passage of unjust criminal laws has sometimes exploited Black labor— as, for example, the Black Codes and convict leasing did for the Postbellum Southern economy. At other times, it has warehoused the "racial neoliberal excess" during labor surplus— as, for example, the three-strikes laws and mandatory minimums did after civil rights made such exploitation formally illegal (Escobar 29). Clearly these historical developments exceed any analogy or single amendment. To combat our current logic of racial disposability, then, we must look farther back than the mandatory minimums and three strikes laws of the 1990s, or the anti-drug rhetoric of the 1980s, or even the economic restructuring of the postwar period. We must also understand how the US penitentiary system developed through liberal ideas about the worth and redemption of white souls.

Indeed, the 19th Century prison was a site of relative privilege even if it was also one of great risk and misery. It functioned through “the alienation of rights and liberties” by removing citizens “from society to a space tyrannically governed by the state” (Davis 44). Because these forms of civil life were not extended to enslaved Africans, many women, and indigenous people in the first place, carceral punishment could not adequately apply to them. For example, Angela Davis has explained that “Women were often punished within the domestic domain, and instruments of torture were sometimes imported by authorities into the household” (41). In 17th Century Britain, “women whose husbands identified them as quarrelsome and unaccepting of male dominance were punished by means of a gossip's bridle, or ‘branks,’ a headpiece with a chain attached and an iron bit that was introduced into the woman's mouth… like the punishment inflicted on slaves, [domestic violence was] rarely taken up by prison reformers” (41-42). And yet now, “With more than one million women behind bars or under the control of the criminal justice system [30% of whom are Black], women are the fastest growing segment of the incarcerated population increasing at nearly double the rate of men since 1985” (ACLU). Once born from ideals of liberal progress, the prison system now increasingly warehouses women and racial minorities without any pretense of reform at all. What explains these extreme transformations?

Although it exceeds the scope of this digital archive, which is so dependent on the holdings at Kroch Library, Southern slavery and penal reform must be incorporated into this history. Naomi Murakawa does this in The First Civil Right wherein she explores the reversal of the "first civil right" between presidents Truman and Nixon to mean, at first, the protection of Southern Blacks from post-emancipation racial terror and then, implicitly, the protection of whites from so-called “gang” violence. Her analysis focuses less on the similarities between slavery and mass incarceration, but rather on how exaggerated differences between these systems of racial control have lent prison expansion more public purchase. As she explains, "Forms of southern criminal justice hold the racial-economic architecture of slavery— from slavery, to plantation-style prison farms, to convict leasing, to chain gangs" (Murakawa 66). Civil Rights Era "progressives" contrasted themselves to this form of criminal justice, and Northern-style penitentiaries thus appeared the solution to racial lawlessness and punitiveness in the South. Like Murakawa's analysis, this digital collection has explored those historical relations of disjuncture and dissimulation that have contributed to our current era of racialized mass incarceration.

Fragments of Reform

The following articles are offered piecemeal, just as they are found in the Kroch Library archive. Statements about these fragments cannot be made with any certainty because they lack so much context and have occasionally withstood physical damage, but if the tumultuous history of prison reform has taught us anything it is that even speculation can be very powerful. When clicked, each item will reveal a different connection between various reform movements and individuals of the 19th Century.

- The Cayuga Patriot and The Cayuga New Era

- Letter from S. Maria Reed to Enos T Throop

- Mrs. Elizabeth T. Porter-Beach address

- Letter to E T Throop from AB Fitch

- Map of Maumee, Ohio (present day Toledo)

- Mr. Kirkpatrick letter

- Mr. & Mrs. J B Varnum address

- St. Luke's Church invitation

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for the support of Cornell’s Grants Program for Digital Collections in Arts and Sciences, most especially the DCAPS (Digital Consulting & Production Services) unit. Without their patience, insight, and problem-solving savvy, this project would not have been possible.

![By Kotepho at English Wikipedia (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7e/AuburnPrisonFront.jpg)